10 Things I Learned While Falling in Love with Big Data

I glanced with disdain at my cell phone as it danced annoyingly on my desk. The year was 2012. Our team had just assumed the reigns for court metadata at Thomson Reuters. I was busy. (Okay, who isn’t?) My irritation quickly evaporated once I recognized the caller. It was my mentor. The newly appointed Vice President of Dockets and Document Retrieval. This was the call I’d been waiting for.

Me: Amy Hrehovcik, here.

New VP: Hey.

So, you know how we assumed it was going to bad? Well, it’s actually MUCH worse. There are over <insert big number> known issues with court content that are not being addressed. And that’s just what we know about.

Do you have any idea how much money this is going to take? Where are we going to get that type of capital?

Amy, I think we made a big mistake.

I remained silent and allowed the words to really sink in. Our current predicament was – arguably – my fault.

When we first met 18 months prior, he was still the Director of Document Research & Retrieval. The man had designed a system capable of finding and moving hard information from point A to point B in four hours or less (continental US). Speed. Status. Experience. At the time, the business was predominantly court retrievals executed for law firms. The lion’s share of revenue was generated in New York City.

Business was good, that is, until New York State went to mandatory e-filing.

The Director knew the business would need an alternative revenue stream, but had been preoccupied addressing unpleasant demand implications impacting the core business (law firms). This is where I come in.

Recruited from finance, I was familiar with capital markets which helped considering our client demographic. Read: I had a lot to learn. Fortunately, the new role came with VIP access to all aspects of litigation information and I had the audacity to use it.

One: Broaden the Vision

18 months were spent immersed in the nuances of court information. From the early-stage pressroom access to complaints, down to the Kansas City archive hunts, and everything in between.

I worked alongside of hundreds of firms and listened to how they interacted with court data. E.g. research, calendaring, new case alerts or tracks. I paid attention to who did what, when, and why. I observed how departments collaborated with one another. What initiatives worked, what didn’t, and why. I inquired into the genesis of high performing teams. I asked about factors contributing to technology partner selection, and listened as clients explained why.

Internally, I soaked up information about other Thomson Reuters Legal (aka Westlaw) offerings. What worked well, what didn’t, and why. And researched competitive offerings as well.

During this time, I recognized two primary things: 1) The biggest differentiator to a firm’s quality of (court) data, speed of delivery, and caliber of end-user decision-making was a function of the process; and 2) The future of court data no longer resided with manual document retrievals. (Admittedly, this one didn’t take a great deal of sleuthing).

Said another way, I wanted in on the future.

Two: Start with a Known Problem

Acquiring court data circa 2012 was a tad more complicated than deploying an algorithm – e.g. Premonition (see Ten: Stay Relevant), or buying one feed fromP.A.C.E.R. Frankly, Federal Courts were easy. State courts were not.

Different software systems, some more reliable than others. Different rules and procedures. Different taxonomies e.g. areas of law, varying degrees of detail. Different processes. Different people. Different skill levels. Different sharing policies. Different prices.

*Math Jargon Alert* Statisticians call this variation. And managing it was a problem.

Also note: it was the end of the Great Recession. A time when municipalities couldn’t keep their pensions afloat. Investing in their e-filing systems was not a priority. Sound familiar? Now, multiply that by 2,000. Literally.

To be clear, Westlaw had the infrastructure to catalog and disseminate dockets and opinions, obviously. (They’d been doing so since the days of the Pony Express.) However, disruption triggered by the Information Age does not discriminate. For purposes of this story, Westlaw had chosen to focus their attention elsewhere.

And I saw an opportunity. (As did Bloomberg Law. Ironically, also in NYC.)

Three: Identify a Champion

I was fortunate in this regard. Not only did I know the right man for the job, but we’d worked closely already. Trust existed. Historic results had been demonstrated. Still, asking him to take responsibility for docket content circa 2012 was no small request.

Begged is a strong word. ‘Implored’ perhaps? By some miracle, he agreed.

Side note: How others view you is important. Do you have a reputation as a problem solver, remover of obstacles, connector of people, and a willingness to serve? If not, do something about it. If so, start with people who trust you already and move from there.

Four: Have a plan

On paper, the to-do list was moderately reasonable.

Front end: address how we acquired court content. More dependable. More frequent. More courts.

Back end: solve for a more sophisticated client profile. More reliable. Better reporting. Prettier delivery options. New functionality. More customizable.

Everything in between: improve existing processes and develop new ones. Cultivate new skills. Reallocate existing resources. Train in-house specialists, Westlaw field representatives, and implementation specialists.

Finally, we would need to make it profitable. Not necessarily in that order.

To be clear, we did not have everything planned out prior to getting started. Many of these details simply were not available yet. But we did not allow unknowns to dissuade us from taking action. We trusted our ability to make smart decisions as they came up.

Five: Use Timing to Your Advantage

Our document research and retrieval business unit finished that first full year at 1,000% of plan. (An awesome accomplishment accredited to an awesome team.) That type of performance demands attention. And it opened the path to many new doors. From there, it was simply a matter of selecting the right one.

Six: Don’t Over Complicate the Business Case

The assumption was we’d need to secure money to improve court data. But until we glimpsed behind the curtain, we had no idea how big the problem was. It goes to logic that quantifying, errr anything, without clearly defining the scope is problematic.

As it turns out, our problem was bigger than we expected. (And the investment required was A LOT more than we could have dreamed.) Unfortunately, we were halfway through Q1 already. Securing unbudgeted investment at a company like Thomson Reuters – mid-quarter – is exceptionally rare (understatement). We knew this, and proceeded anyway.

The team prepared a state-of-the-union synopsis to demonstrate the scope of business problem. We paired that with one slide (that could have been compiled by an 8th grader, albeit a gifted one): a) Revenue generated from services that Do Not Function without quality court data; and b) Revenue generated from services that Do Not Function Well without quality court data. This one visual changed the way I perceived business cases moving forward.

The size of investment required to address known needs will dwarf in comparison when prepared properly. For us, our investment ask – despite starting with a ‘m’ – was less than 1% of the potential revenue impacted.

We didn’t allow precedence to dissuade us from trying. We kept it simple. We made it visually appealing. It was presented well. And we got the money we needed. (This was a good day.)

Seven: Assess the As-Is

I’ll spare you the Google Maps analogy. Everyone knows the darn thing can’t tell us how to get to our destination until we enable the location setting. (If you’re like me – constantly turning it off to preserve battery – you get reminded a lot.)

This translates into phase one and phase two: define and measure the process.

I cannot over-emphasize the impact assigning names and definitions had for us. E.g. three types of court scrapes: database, gateway, and index. Six docket systems across Westlaw. Three types of court notifications: early-alert, alert, and track. It’s simple to do, and does not cost a dime. It so simple that most perceive it to be unimportant. This is a mistake. From here, we were able to apply them consistently and communicate effectively.

Terms that are easily understood and consistently applied inject order into mayhem. They empower diverse teams by enhancing understanding. They work.

Re measure the process, I’ll refer to the early-alerting service we also acquired. Humor me a quick overview. Monitoring new cases had become standard operating procedure. That said, not all court alerts are created equal. One way to differentiate – and this applies to both buyers and sellers of information – is through speed and precision targeting. The speed of intel is received, the speed it arrives on the desk of the individual who sees it and is confident enough to act on it.

Alerts triggered from pressroom access to complaints are faster than those coming from the e-filing system. Lead-time varies depending on the strictness of each court’s press room. At the time, Southern District’s pressroom had a 3 to 5 day head start. (Prior to the complaints being uploaded into P.A.C.E.R.)

Also note: press badges at court houses are tough to come by. I equate it with securing a liquor license in NJ. (Someone has to physically die in order to do so.) When Thomson acquired Reuters circa 2007ish, they inherited badges across the country.

Full disclosure: Westlaw had built a system prior to our team stepping in. But it didn’t work very well. More importantly, it was not profitable. (Ironically, the idea was originally submitted to Eagan, MN by the guy that ran Operations in NYC for the Document Research and Retrieval Team. My very close colleague and friend.)

I spent days at Southern District shadowing our representative, with a stop watch. I stood amongst eager reporters as they migrated – three times a day – from their desks in the pressroom to the clerk’s station to collectively receive one pile of complaints. I observed how our teammate inputted her portion into our system, and how she switched piles with others after the fact. I listened to her suggestions as to how we could move faster. And I reported the insight back up.

Eight: Don’t be Afraid to Make Mistakes Test and Pilot Everything

We did A LOT of testing. E.g. the setting of new case alerts. In order to generate a “hit” historically, the spelling of a company name at the creation of an alert needed to match the spelling on the docket sheet:

J.P. Morgan = J.P. Morgan = alert

J.P. Morgan ≠ JP Morgan = no alert

JPMorgan ≠ JPM ≠ J.P.M. = no alert

Similarly, misspellings on the docket sheet (accidental?) and/or subsidiaries that did not include the parent company’s name also went undetected.

In order to combat challenges, it became common practice to set 10 plus alerts for one single client.

10 alerts x 10 clients = headache

10 alerts x 100 clients = nightmare

Enter ticker symbols. Using ticker symbols to set alerts would alleviate a great deal of pain for our clients; if the team could guarantee effectiveness. (Testing this feature took four months, but we got there.)

Product functionality wasn’t the only thing we tested. We explored different ways to trial the content as well. Unlike most Westlaw trials, accessing and disseminating court intel incurred expenses, and these costs varied from court to court. (Note: we needed to test different pricing scenarios as well.) Doing the math on where / when to conduct a trial was extremely important.

The best type of trial was also up for debate. Westlaw has numerous ways to trial content, most common being individual (trial) passwords. While temporary passwords were easy to issue and simple to deactivate, they weren”t as effective: 1) setting alerts and tracks was too time consuming to just ‘deactivate’ at the conclusion; 2) recipients of case alerts would need to be able to access content on personal WL passwords and inevitably ‘out of plan’ charges would ensue; and 3) our court information systems were designed to support teams of people. Individual trial passwords would not be able to demonstrate group efficiency.

We figured it out, but there were growing pains. (One particular five-digit client credit comes to mind. Especially painful considering it was noticed and requested one month after the quarter had closed.)

Nine: If you build it, they won’t necessarily come (Same applies forbought it or implemented it.)

Wouldn’t it be lovely to live in a Field of Dreams? Sadly, this is the real world where changing behaviors is hard work.

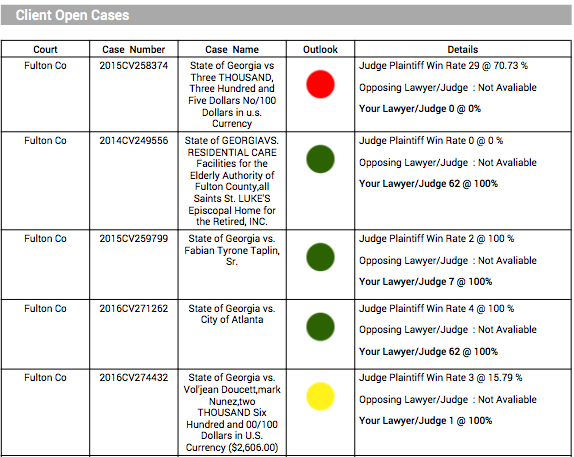

Take Monitor Suite as an example. A Thomson Reuters tool given to our team nine months into our court data tenure. The flagship component being Litigation Monitor. Within Lit. Monitor was a newly-developed add-on feature called Case Outcomes. C.O. boasted an ability to “predict” (term used loosely) case resolutions – e.g. Summary Judgment, Motion to Dismiss, Settlement, or Trial – and medium time required to do so. And it wasn’t selling. Again confirming, new systems, software, dashboards, reports, newsletters, etc. are all equally easy to ignore.

Addressing this lack of adoption began by understanding the psychology of resistance.

If I’m a litigator operating in said jurisdiction for 25 plus years, I’ve earned the right to know how a judge is likely to behave. Or the strategy an opposing counsel likely to take. Why would I invest in a piece of technology that would seemingly diminish my value? (Especially when I’m still paid by the hour.)

Once we understood the root cause problem, we designed the messaging and support materials to help others overcome resistance and incorporate the intelligence into decision making.

Ten: Stay relevant

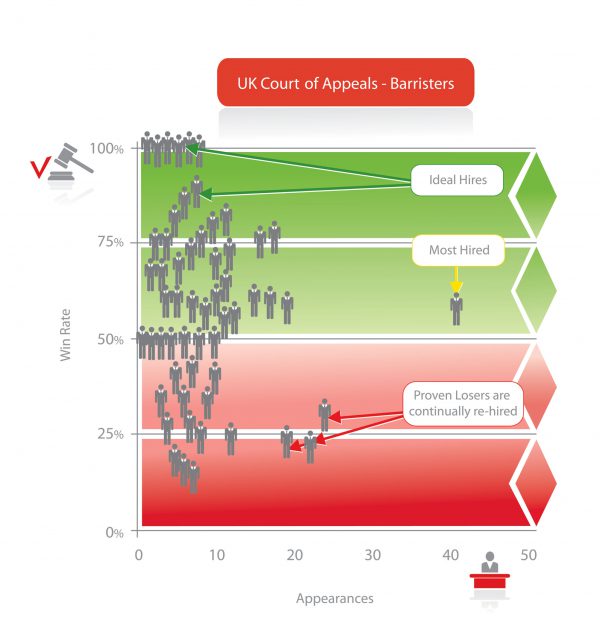

A lot has changed in the court data game since 2014. Specifically Premonition. The company that redefined the data-gather process. Overnight.

Read: an effort that required hundreds of thousands of dollars LAST YEAR – people, salaries, time, court contracts, prices, normalizing, and more; is now being done with an algorithm. A faster, cheaper, more accurate proposition that allows Premonition to spend their capital elsewhere.

For legal industry readers: imagine the possibilities if we were to apply the same logic to normalizing historic matter data. Or “scrubbing” our client data (CRM system). Note: advanced firms are doing this already.

Too often, we allow our biases and past experiences to limit our perception of what’s possible. Our ability to control said biases is what differentiates us.

If your organization is solving for today’s business problems the same way they’ve always done, chances are you’re over-spending.

Keep an open mind. Seek out those with different experiences and perspectives. Invest in ‘measure twice’ assessments in order to best ‘cut once’.

Final thought:

In my last year at Thomson Reuters, we did enough dockets business in that first month to cover an annual sales quota (#Winning). Another awesome effort accredited to an awesome team. I”m thankful for the “Big” (data) doors my Thomson Reuters career has opened since then. And I look forward to what”s still to come.

With six weeks remaining in the year, it’s time to get serious about 2016. For those of you — like me — reflecting on which business problems to address in 2016 and how to best solve them… Consider this:

The term Big data is misleading.

Size has nothing to do with it. Today, information moves. It’s what you do with it that counts.

Bridging historic data structure with present day application calls for new skills, new workflows, and new vision. **Spoiler Alert** algorithms will not empathize with peers as they figure out how to use it (yet).

People help people use data. People help organizations solve business problems. People ask questions and listen to the needs of others. People shift perspectives of organizations. Sure, data quality and system connectivity are important, but focusing too intently on data’s lack of structure is not the start.

When people have access to information — that is easily understood — they make smarter decisions.

For those of you aspiring to lead on the information front, it begins by honing your skills through experience. Consider first helping others use the data you’ve got. From there, ‘Big’ data is simply your spark.

By Amy Hrehovcik, Founder of Ailey Advisors