Moneyball

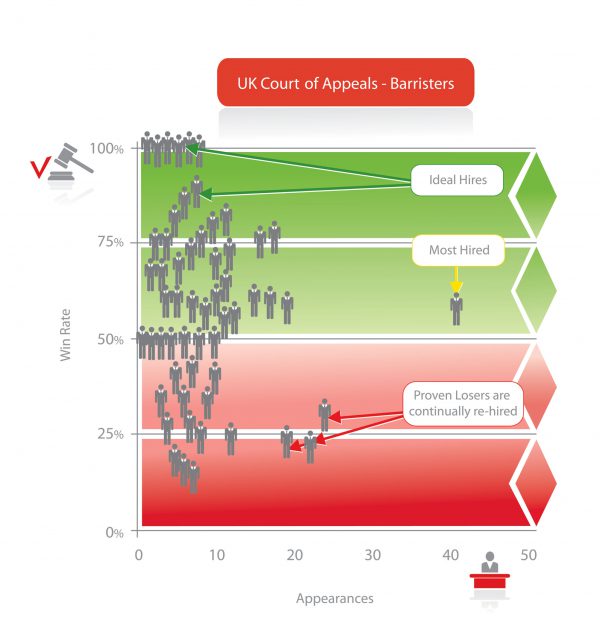

Here’s a joke for you: What do you call a man who bets on instinct? Give up? A mug. Here’s another: What do you call a lawyer who instructs Counsel without really having the faintest idea as to that barrister’s success rate? Answer: the entire legal profession.

I accept that the above material does not make me the natural successor to the late comedy genius David Nobbs (although I have been called his surname on numerous occasions ) but what it does show is that lawyers and indeed claimants pay scant regard to the success rate of their chosen legal professionals when giving their instructions. I have argued previously that the prospects of success expressed by Counsel in their Opinions are pretty meaningless unless you know their track record. If Counsel says that my case has a 75% chance of succeeding and I know that he or she is correct 80% of the time from a sample of 100 cases, then I can start to feel pretty good about life. If, however, I receive the same assessment from someone who is incorrect most of the time, then I ought to be looking elsewhere for an Opinion to see whether my case is really as strong as predicted or if I am better off making a hasty exit.

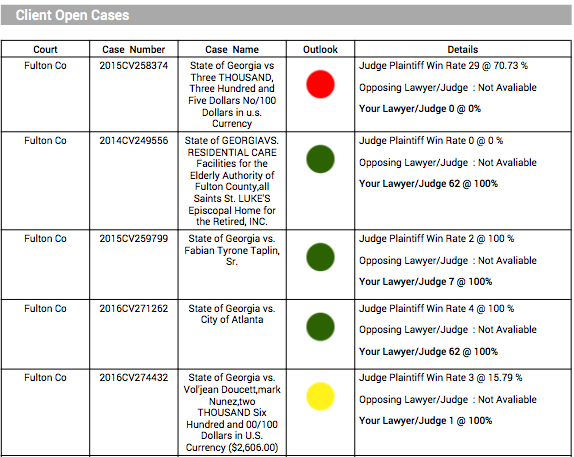

Florida-based Premonition, which analyses the win rates of attorneys across the United States has conducted what it regards as ground-breaking research in the UK which it predicts will revolutionise the legal market in this country. It studied 11,647 High Court and Court of Appeal cases between 2012 and 2014 and named Hewitsons, Monckton Chambers, and Michael Fordham QC as being amongst the top performers. Premonition’s Toby Unwin argues that this type of ‘Moneyball’ legal analytics represents the future of the legal industry as it is by far the best measure of individual effectiveness available anywhere.

When the list was published a few weeks ago, it was met with howls of derision from a profession keen to distance themselves from the harsh glare of external scrutiny. The usual arguments were put forward: firms have no real choice about what cases they take on, chambers specialising in public law are more likely to appear before the Courts (and therefore on the list), cases ending up in court are actually a metric of the firm’s ‘failure’ to agree a settlement etc. Questions were also raised about what constitutes a ‘win’.

All of these objections are not without merit. The best metric of success is undoubtedly the ability of a firm or Counsel to agree a commercially acceptable settlement for its defendant or claimant client and in so doing, incurring the lowest possible legal costs. Such settlements are invariably achieved on confidential terms, however, so it is highly unlikely that such data will ever be subject to external scrutiny. That said, the sheer size of the data sample analysed by Premonition ought to dispel many of the concerns about adverse case selection – you might not like it, but you cannot ignore it. Whether you agree with Premonition’s conclusions or not, the data is showing us something.

Statistics are part and parcel these days of lots of activities previously regarded as ‘unquantifiable’. The most obvious example is professional sport where a smorgasbord of numerical data is used to quantify and rank performers in golf, horseracing, tennis, rugby, baseball, American Football etc. Football managers active in the transfer markets will invariably call for their intended target’s ‘stats’ before even bothering to send a scout to watch them play. Pass completion percentages, pass assists, goals, interceptions etc. are just another tool at the disposal of the modern manager in helping him decide whether a player represents value for money. And that’s just it – statistics are a tool, a guide to help make sense of a subject which apparently defies quantification. They are not a substitute for the football manager’s skill and experience but they are a guide to inform him of where not to invest his time and money.

The worst thing that can happen now is for Premonition to abandon their analysis. Their exercise will win over the undecided by virtue of repetition: the more the exercise is undertaken month on month, year by year, the greater its credibility. And the bigger the sample size, the harder it will be for people to argue that it is flawed.